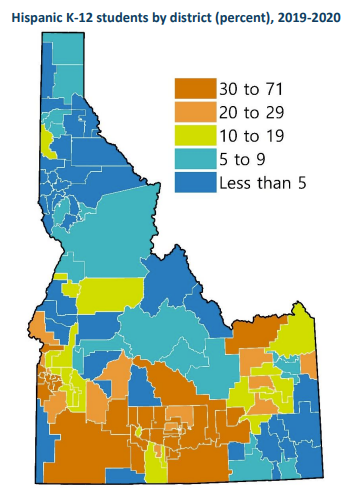

Education Equity for Latinx Students in Idaho

Last updated on February 21, 2023

Education Equity for Latinx Students in Idaho

The Education Equity for Latinx Students project started in the fall of 2022 as part of our efforts to expand racial justice work on behalf of Idaho students, beginning with Latinx communities.

The Education Equity for Latinx Students project started in the fall of 2022 as part of our efforts to expand racial justice work on behalf of Idaho students, beginning with Latinx communities. Through an ongoing series of community listening sessions and interviews, we continue to learn about the unique and shared experiences of Latinx students in Idaho classrooms. Our leading question going into this work is “What obstacles are you facing as a Latinx student or parent, or as an educator serving Latinx students?” Our hope is to learn about many more Latinx students’ experiences, document these stories through our Education Story Collection efforts, and report on our findings.